In the garden with chef Greg Higgins

Portrait of Portland, Winter 2014

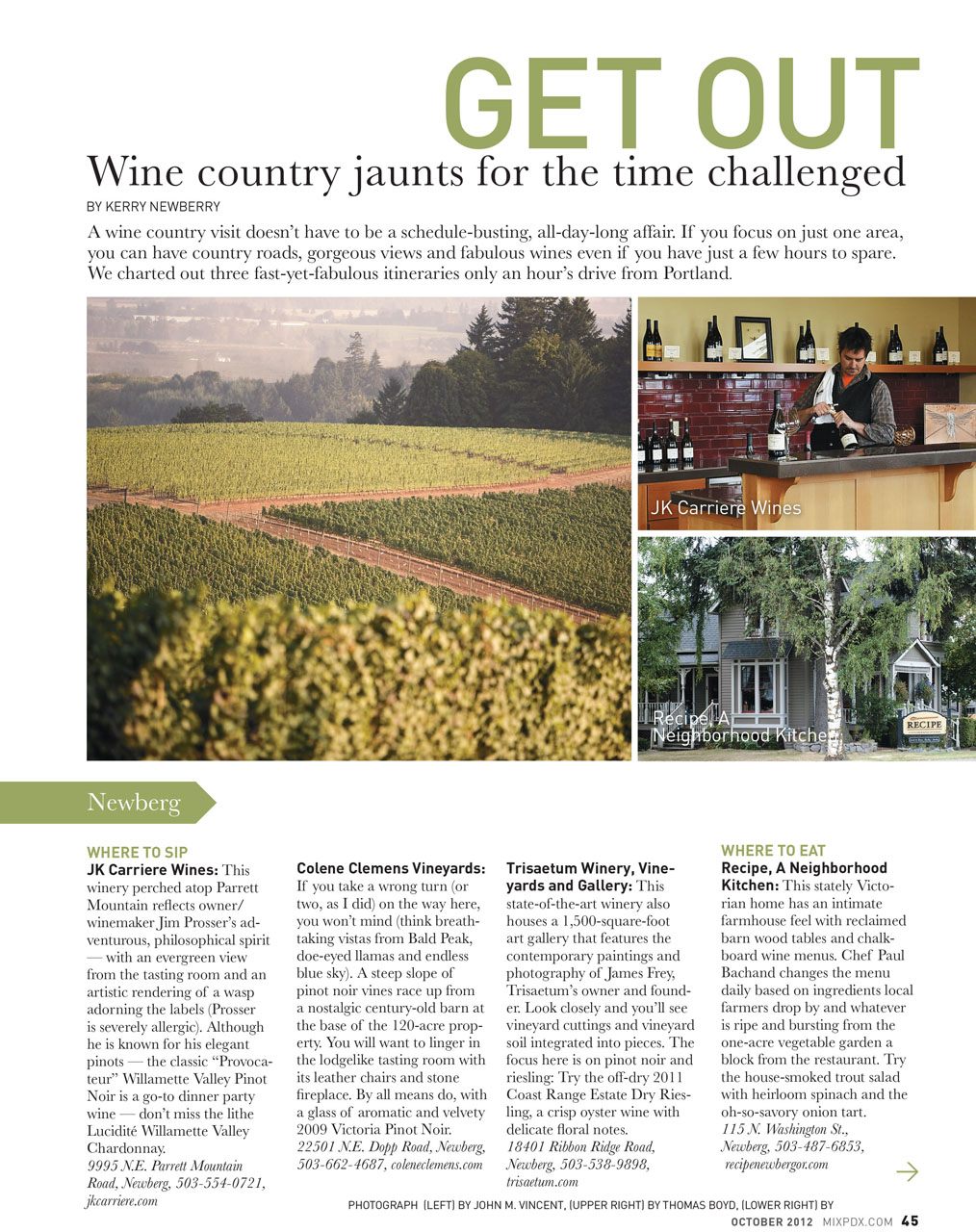

“One of the most delightful things about a garden is the anticipation it provides,” wrote English author W.E. Johns. This anticipation, plus insatiable curiosity and creativity is why you’ll find chef Greg Higgins in his home garden rain or shine, summer through winter. “It’s become a lifestyle,” says Higgins, the godfather of farm-to-table dining in Portland—which he has been cooking up at his eponymous downtown restaurant Higgins for nearly two decades.

“It’s much more exciting for me to cook with food when I know where it came from and what it took to get it to the kitchen,” says Higgins. “Whether it’s at home, or at the restaurant.” Higgins grew up in a small farm town outside of Buffalo, New York. “We had a big family garden and I worked on farms as a kid,” he says. “I was always close to how food grew.”

When the chef was cooking in Seattle in the 1980’s, he met Angelo Pelligrini, a Washington State University professor and author of books advocating for fresh, simple ingredients and the pleasures of growing and making your own food and wine. His first book, The Unprejudiced Palate was published in 1948 and is still touted as a classic by great chefs today.

Pelligrini had an amazing house with the ultimate peasant garden, says Higgins, lush multi-layered tiers of edible plants, shrubs, fruit trees, herbs and ornamentals. “I was inspired by him and thought when I have a house I’m going to do what he did,” he adds. In his backyard, Higgins has created more than a prolific kitchen garden, he’s architected a Zen-like oasis. Mystical statues from travels across the globe (think China, Japan, Morocco) peek from leafy edibles sprouting in pots.

A wanderlust in the name of food, Higgins has cooked in kitchens around the world. Two years ago, he ventured to Mongolia when the aid agency Mercy Corps asked him to spend three weeks teaching sausage and charcuterie-making to cooks—a journey, that like the garden, sparked ideas for dishes with an exotic touch.

Devotees of the downtown restaurant may already know that heirloom chili peppers are one of his secret ingredients—it’s the flavor you just can’t put your finger on. “We make an orange and chili-infused ice cream that’s mind blowing, it tastes like a rare tropical fruit,” says Higgins. Every savory dish in the restaurant contains chili peppers of one sort or another—from the fruity fatalii to the herbal aji dulce.

“To me they are one of the trinities of basic flavor,” he explains, “chili, garlic and olive oil.” For two decades, Higgins has collected seeds for rare and heirloom chili peppers. Every February he plants a half-acre garden at home for test cropping with about 600 chili and tomato plants as seedlings, all pure varieties.

“I’m crazy for rare varieties of tomatoes and peppers,” he says. He saves seeds from the chili plants he’s excited about, passing them on to growers to expand production the following year. “It’s a philosophy,” says Higgins, “I believe in the whole cycle of food, from seed to table and back.”

The remaining starts he gives to employees, and customers, to spread the gospel of gardening. “Even if they just have a porch—put it in a bigger pot, water it, take care of it, see what you get,” he says. “I like to get people to know where there food comes from. This is my way to connect.”

The garden, for Higgins, is an incubator for the restaurant and hard-to-find ingredients. “I don’t know what it is, but I have this fascination with growing things I really shouldn’t be able to grow,” says Higgins, as he stands next to a vibrant yuzu plant, a highly fragrant Japanese citrus fruit not commonly found in Pacific Northwest gardens. “It’s a curiosity.” Note: a sensational Sichuan pepper also bursting nearby.

In addition to a medley of potted citrus, waxy green pardon peppers and his tanks of chili peppers, Higgins tends to three olive trees—one, the Arbequina, was a gift from a Growing Gardens fundraiser dinner ten years ago. His two-acre terraced garden springs with basics, too, from asparagus to zucchini.

Try this, he says, as he plucks a heart-shaped leaf from another heat-loving plant thriving in his garden. It’s Malabar, a plant that hails from the tropics with leaves that taste like a cross between spinach and okra. “The flower buds pickle into tasty little morsels,” says Higgins.

The chef continues the tour, winding around a 75-year old apple tree, with squat knotty trunks, the flush pink blossoms a summer memory. When the apple tree loses leaves, these beds are bathed by winter sunlight, says Higgins, as he points to black earth that will sprout green in a few months with leeks, kale, artichokes, overwintering broccoli and cardoons.

The exquisitely landscaped garden is fluid, and texturally flows like a Monet painting. “I’m always thinking of things overlapping, not sequentially,” says Higgins. “Because of my background in art, I’m very much of a relational thinker.” Many lessons have been gleaned from working the soil over the past twenty years; after two decades you really get to know what you can and can’t do, he says.

In that sense, “gardening is also a story of failures,” says Higgins. “That’s how you learn. You learn when the plants thrive, but you also learn dramatically when they fail. When you are in one place long enough, you really get more of a hold on that.”

The tranquil flow of water streams from a Zen-like fountain, in tune to the pitter-patter of the family corgi walking by. Higgins steps under the pergola he built from repurposed barrel fermenters—where in the springtime, purple wisteria blooms tumble from the beams. He stokes a warm fire from the pièce de résistance of the garden patio–a wood-fired oven for his bread-making and impromptu pizza nights.

As he begins kneading dough for flatbreads (one component to a Mediterranean feast that evening) he muses about the role the garden plays in the restaurant. “We can be out picking mushrooms, come home and look in the garden and decide we’ll pair this with that,” he says. Eventually, the most memorable dishes will end up in the restaurant. “Dinner for us and our friends then turns into dinner for the city of Portland.”