Winery Spotlight: Abacela, Roseburg, Oregon

Sommelier Journal, October 2011

A winemaker’s love of Spanish varieties has blossomed in Southern Oregon.

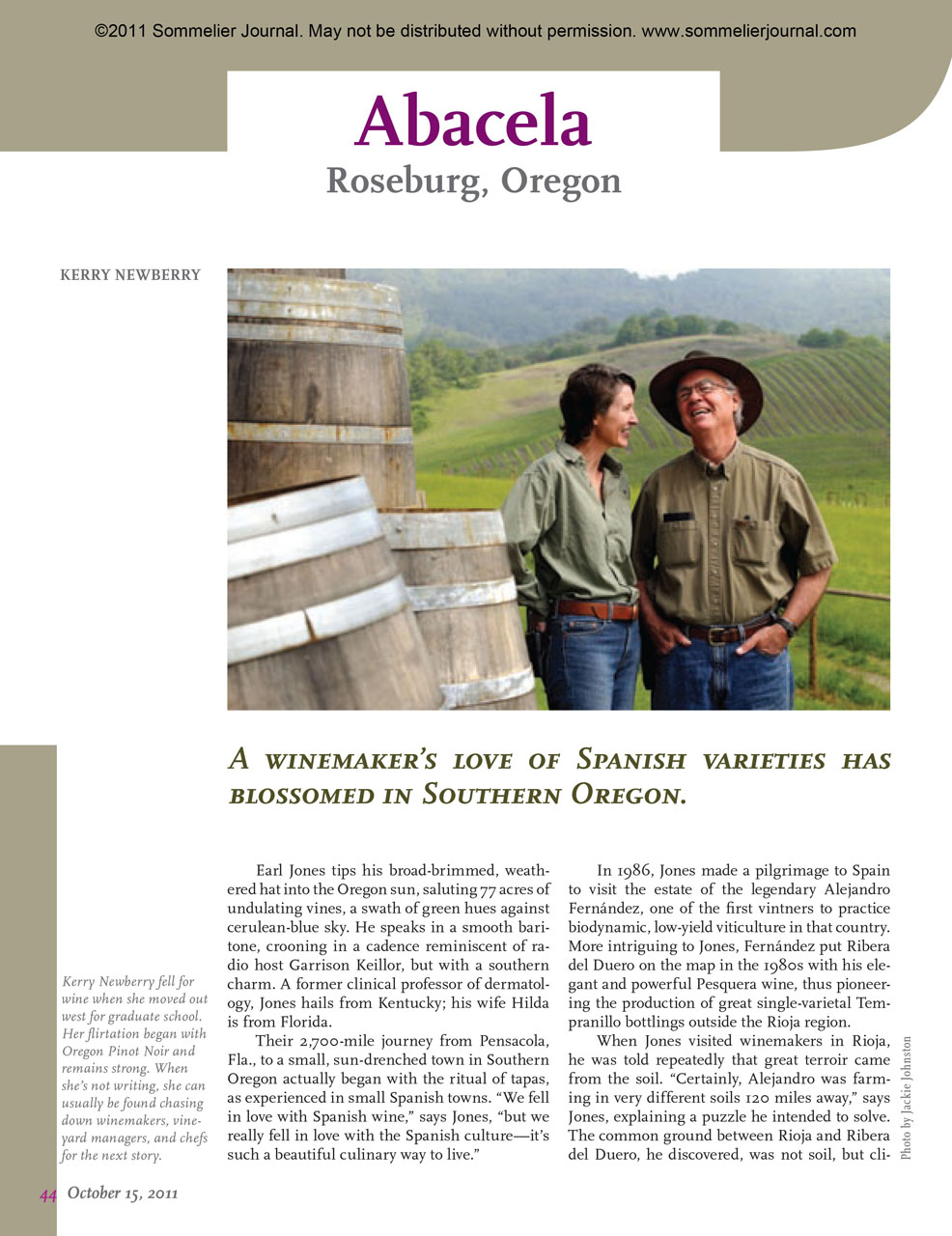

Earl Jones tips his broad-brimmed, weathered hat into the Oregon sun, saluting 77 acres of undulating vines, a swath of green hues against cerulean-blue sky. He speaks in a smooth baritone, crooning in a cadence reminiscent of radio host Garrison Keillor, but with a southern charm. A former clinical professor of dermatology, Jones hails from Kentucky; his wife Hilda is from Florida.

Their 2,700-mile journey from Pensacola, Fla., to a small, sun-drenched town in Southern Oregon actually began with the ritual of tapas, as experienced in small Spanish towns. “We fell in love with Spanish wine,” says Jones, “but we really fell in love with the Spanish culture—it’s such a beautiful culinary way to live.”

In 1986, Jones made a pilgrimage to Spain to visit the estate of the legendary Alejandro Fernández, one of the first vintners to practice biodynamic, low-yield viticulture in that country. More intriguing to Jones, Fernández put Ribera del Duero on the map in the 1980s with his elegant and powerful Pesquera wine, thus pioneering the production of great single-varietal Tempranillo bottlings outside the Rioja region.

When Jones visited winemakers in Rioja, he was told repeatedly that great terroir came from the soil. “Certainly, Alejandro was farming in very different soils 120 miles away,” says Jones, explaining a puzzle he intended to solve. The common ground between Rioja and Ribera del Duero, he discovered, was not soil, but climate. “Really, the major component of terroir is climate,” says Jones. “Soils come in second. We knew that if we grew Tempranillo in America, it wouldn’t be in Spanish soil, and the next best thing we could do was try to find the most identical Spanish-like climate that we could.”

Jones turned to his son Greg, who was in graduate school at the time and is now an internationally respected professor and research climatologist in the department of environmental studies at Southern Oregon University. After poring through books, climate records, and maps and touring winegrowing areas throughout the American West, they settled on Jackson, Josephine, and Douglas counties in the Umpqua Valley of Southern Oregon. Roseburg, Ore., was a near-perfect climatological match to the north-central and northwestern portions of the Iberian Peninsula, including Rioja and Ribera del Duero.

Jones found a 19th-century homestead for sale in Douglas County, 11 miles southwest of Roseburg, and there, on a south-sloping hillside called Cox’s Rock, he planted his first Tempranillo in 1995. He named his winery Abacela—from an ancient Latin-Iberian verb, abacelar, meaning “to plant a grapevine”—as an homage to the wines of Spain. Abacela produced the first commercial Tempranillo from the Pacific Northwest in 1997; only three years later, its 1998 Tempranillo Estate secured the first U.S. victory for the variety in the San Francisco International Wine Competition, besting all Spanish entries. More recently, in 2009, Abacela won America’s first Meda-lla de Oro (gold medal) for a varietal Tempranillo in Spain’s own Tempranillo al Mundo competition.

Tempranillo thrives in what Jones calls “the Southern Oregon mesoclimate,” which registers an annual average of 2,700 degree days. A long growing season and cool autumn allow the grape to ripen perfectly without excessive sugar accumulation. Encouraged by his early success and guided by a book by John Gladstone, Viticulture and Environment, Jones planted complementary varieties such as Malbec, Merlot, and Dolcetto in the same block.

Albariño was a different story. In Spain, it’s the principal white grape of Galicia—the northwest corner of the country, resting above Portugal and hugging the Atlantic Ocean. But from the second-floor balcony of his Abacela Vine and Wine Center, Jones can point to Albariño vines rambling down the cooler north slopes of the subtly peaking terrain. That aspect reduces sun exposure, allowing the grapes to ripen slowly while retaining lively acidity. “What’s remarkable at Abacela is we grow both of the grapes to a level of excellence that’s on par with Spain, and we do so in the same vineyard,” says Jones. “Rioja and Galicia are about 350 miles apart; at Abacela, they are about 500 feet apart. That really defines our terroir.”

Abacela subscribes to the Low Input Viticulture and Enology (LIVE) standards for sustainable farming, and its vineyards are certified Salmon-Safe, as part of a program dedicated to restoring and maintaining healthy watersheds. A strong believer that the character and quality of a wine are made in the vineyard, Jones built a three-level, gravity-flow winery to eliminate unnecessary manipulation. He uses whole-berry fermentation for aromatics, along with cold soaking, manual punchdowns, and a basket press.

On the balcony, Jones swirls a glass of the watermelon-hued 2010 Grenache Rosé, made from grapes grown on the same slopes as the Albariño. “Man could live on bread and wine alone,” he muses. Fresh-baked sourdough bread sits on a nearby table, still warm from the Spanish wood-fired brick oven—the same oven used to prepare tapas for Abacela’s terroir-driven tastings. It’s all part of bringing the flavor of Spain to Southern Oregon.

Abacela

12500 Lookingglass Road

Roseburg, OR 97471

(541) 679-6642

www.abacela.com