How the pros taste: Quality control with Willie-Yli-Luoma from Heart Roasters in Portland

Each morning around nine, Willie Yli-Luoma heads to the basement of Heart Coffee Roasters for QC (quality control). Here, that means tasting through about ten cups of coffee—all before he’s had one to drink.

A former pro snowboarder from Finland, Yli-Luoma developed an obsession with coffee soon after settling in Portland. In a city with a coffee shop on every block, he migrated from one micro-roaster to the next, tasting for character and consistency.

As his zeal for coffee grew, so did his gadgets—the deluxe espresso machine that swallowed his home kitchen had the capacity to brew 480 cups per hour. More than enough to learn to pull the perfect shot.

In between surfing, mountain biking and gliding across snow-capped peaks, he began buying green beans to roast in his basement. The tenacity required for an effortless 360-degree spin on the slopes, now turned to honing his palate with frequent, meticulous tastings.

After two years of experimenting with single origin coffee beans, he scored a 1953 Probat from the Netherlands—a large and impressive roaster that’s one of the most well-known in town—and opened Heart Coffee Roasters and Café in Portland in 2009,

Since then, he’s developed a loyal following for his roasts, a lighter style than most in the city. “When you roast coffee darker, you get more bitterness, and you lose sweetness,” he says. “I’m very sensitive to bitter flavors, that’s why we handle our coffee a certain way,” he adds.

Maintaining a consistent style when roasting daily requires a level of rigor that seems to come naturally to the former pro athlete, judging from his efficient, calculated approach to tasting. In his basement coffee lab, he chats as he taps in data with his right hand and clicks on an electric kettle with the other.

He begins by measuring out whole-bean coffee using a digital scale, weighing eleven grams of coffee and 177 grams of water for five beans with two roast profiles. As the water heats, Yli-Luoma grinds the beans using a copper-hued Malhkonig EK43, a grinder that was originally developed for milling spices, and quickly adopted by specialty coffee.

“It’s very good for QC,” he says. “This gives us the most even grind particle size and also allows us to focus more on the coffee versus the extraction.” He grinds for each glass individually, brushing the grinder between batches to prevent cross-contamination.

Next, he smells the dry grounds. “We look want lots of good aromas—fruity, chocolate, floral, and sweet stuff,” he says. “And hope not to smell things like wood, peanut, earth and jute, which are all negative aromas.”

Then he adds the 205F water, pouring slowly and methodically, making sure all the coffee grounds get saturated.

After the hot water hits the grounds, he starts his digital timers, and sidles slowly from cup to cup, sniffing deeply. As the coffee steeps, the grounds rise to form a thick crust that resembles a crumbled chocolate cookie (CK and what happens with the aromas over that 4-minute period? I imagine they sort of “bloom”—so what’s he looking for as he does this?

When the first timer marks four minutes, a standard time for extraction (CK: “standard time” doesn’t really tell me anything—why do most people do it that way? Is that the average time it takes for the grounds to release all their flavor?,

Yli-Luoma breaks the crust of the first cup, gently sweeping a spoon through the grounds, releasing a burst of coffee aromas. “It’s important that you break the crust in a very similar way for each cup,” he says.

At this point, he’s evaluating for defects. “I’m looking to see if I can smell any raw, vegetal flavors, straw or grass—those are things I want to avoid,” he says. Those aromas mean that the coffee was under-roasted. “If I smell any rubbery flavors, that means the coffee beans got too hot.”

He bobs between cups, inhaling deeply at each one. “Now you can really get an idea of what that coffee is going to be like,” he says. “The tasting is the most important part,” he adds, “but a big part of the sensory experience is also found through aroma.”

This explains the two tenets Yli-Luoma follows on coffee bean procurement travels to Latin America or Africa, where he tastes up to 100 cups of coffee a day. “I don’t eat any spicy foods,” he says. “And I go for a run in the morning, because it really opens up my sinuses.”

The second timer goes off at 12 minutes—about the time that it takes for the coffee to be cool down enough to taste. Then he skims each cup clean of grounds for tasting. “The sooner you can taste, the better,” says Yli-Luoma. “Because the coffee is evaporating aromas into the air versus your mouth,” he adds.

Rather than picking up the cup, Yli-Luoma picks up a spoon he dips into the coffee and sips from. “It’s so we can slurp air at the same time and spread the coffee around the mouth,” he explains “When we travel we meet people with crazy loud slurps, like whistles and things. I’m more of a softer slurper,” he adds.

“I look for sweetness, acidity and clarity,” says Yli-Luoma, rinsing his spoon in a glass of warm water before he dips it into the next cup. He tastes through the circuit multiple times; the coffee’s flavors and character changing as they cool down to room temperature.

He’s also looking for what he calls “personality,” a sense of where the beans came from . “To me, this tastes like an Ethiopian coffee. I get floral qualities. There’s a little bit of honey, a little bit of citrus. This is I would say a classic Yirgacheffe coffee,” he says.

He slurps one more time, and then adds: It’s our Borboya. These heirloom coffee beans grow at over 6,000 feet in Ethiopia’s southern highlands. “We use it 50 percent in our house espresso—it’s sweet, clean, transparent,” says Yli-Luom. The high altitude microclimate yields pronounced and distinctive flavor profiles.

The next cup, he guesses, is from Nyeri in Kenya. “Kenyans usually have the heaviest mouth feel, also the highest acidity,” he says. “The fruits are really intense,” he explains.

For Yli-Luoma, coffee should not merely taste good; it ought to also offer a portrait of the place it came from, and what it has to offer in flavors and aroma. “When you brew the coffee with different methods, you might not always find all of those flavors. If you are brewing the coffee wrong, you will not find any of those flavors.”

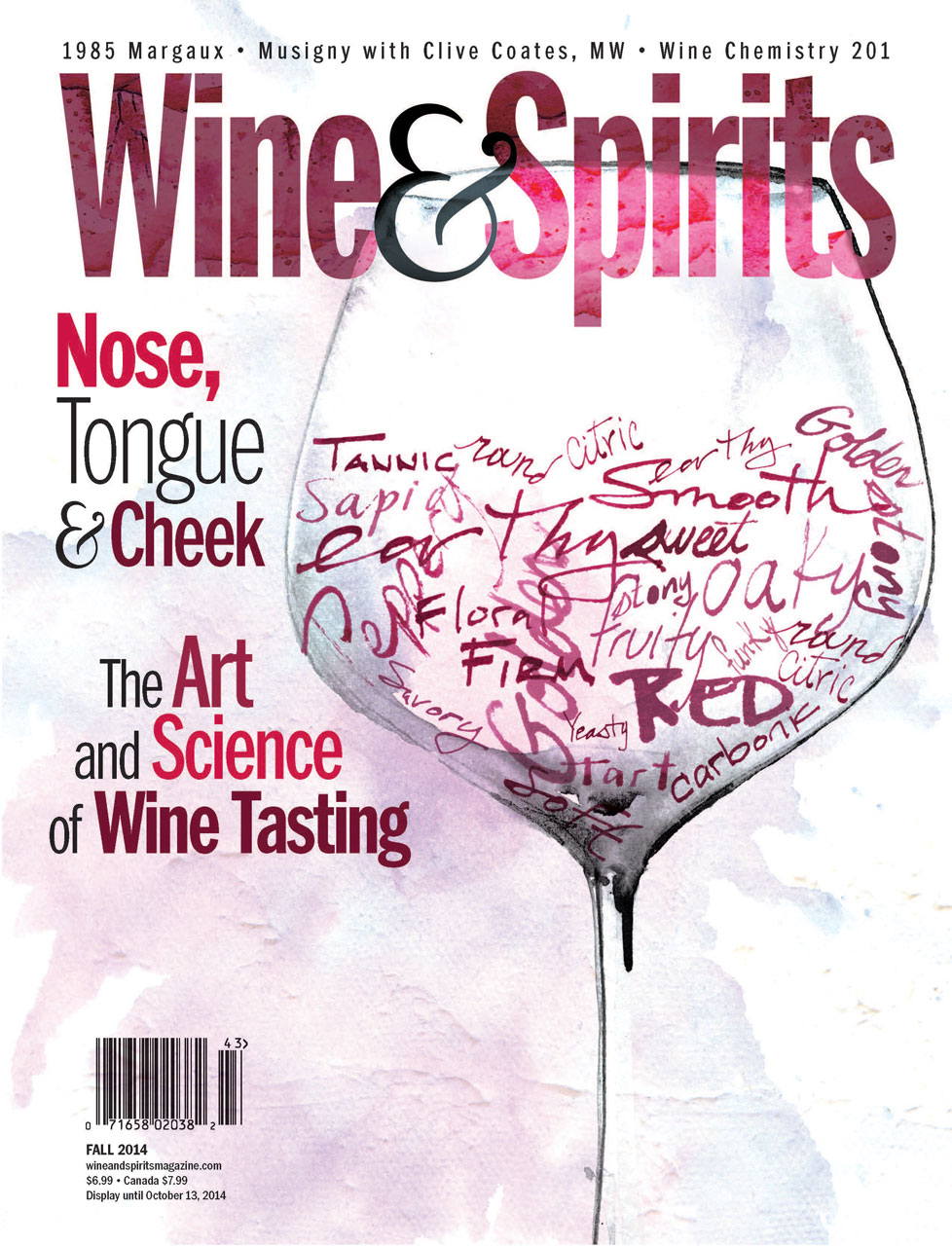

Wine & Spirits Magazine | Fall 2014

wineandspiritsmagazine.com