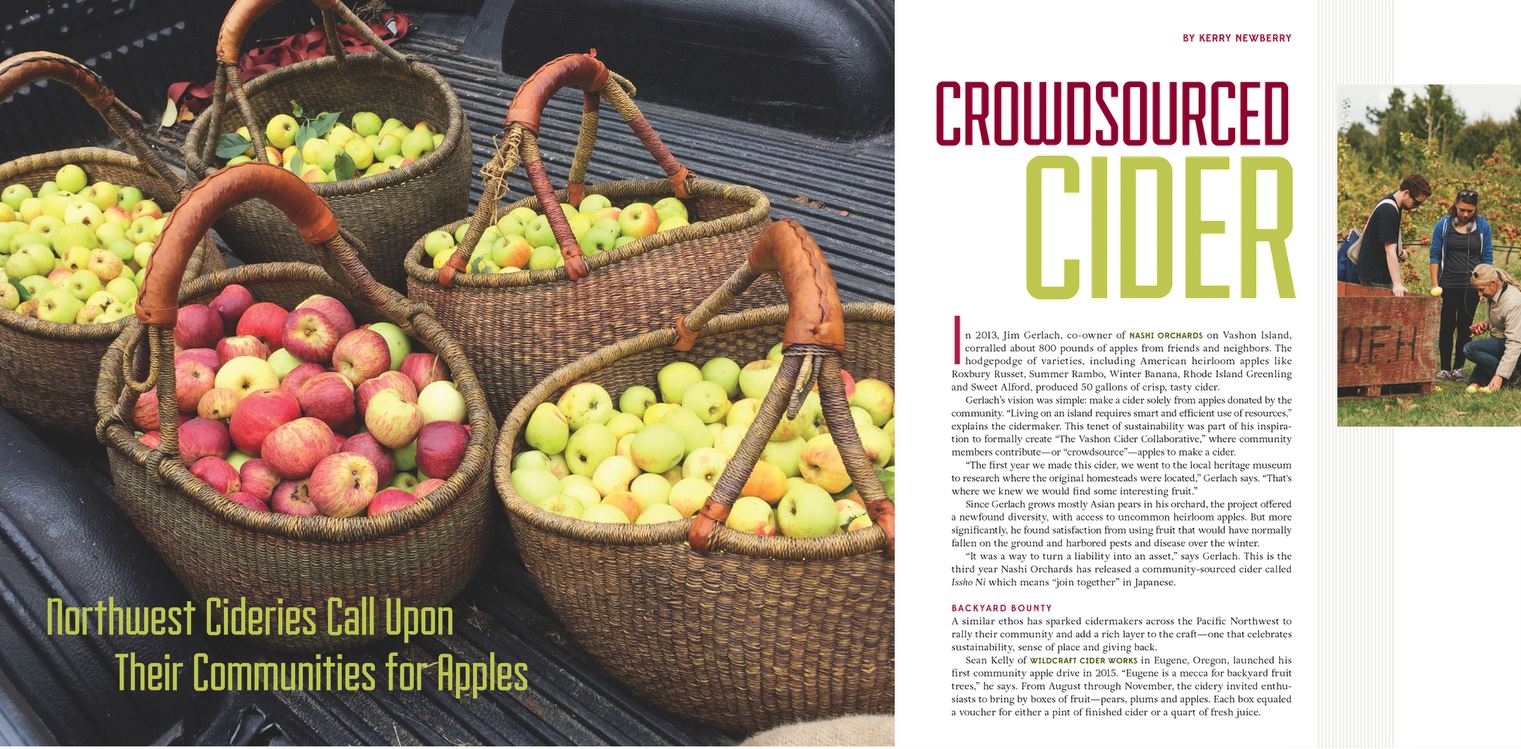

Crowdsourced Cider: Northwest Cideries Call Upon Their Communities for Apples

In 2013, Jim Gerlach, co-owner of Nashi Orchards on Vashon Island, corralled about 800 pounds of apples from friends and neighbors. The hodgepodge of varieties, including Roxbury Russet, Summer Rambo, Winter Banana, Rhode Island Greenling, and Sweet Alford produced 50 gallons of a crisp, tasty cider.

Gerlach’s vision was simple: make a cider solely from apples donated by the community. “Living on an island requires smart and efficient use of resources,” explains Gerlach. This tenet of sustainability was part of his inspiration to formally create ‘The Vashon Cider Collaborative,’ where community members contribute—or “crowd-source” apples to make a cider.

“The first year we made this cider we went to the local heritage museum to research where the original homesteads were located,” he says. “That’s where we knew we would find some interesting fruit.”

Since Gerlach grows mostly Asian pears in his orchard, the project offered a newfound diversity, with access to uncommon heirloom apples.

But more significantly, he found satisfaction from using fruit that would have normally fallen on the ground and harbored pests and disease over the winter. “It was a way to turn a liability into an asset,” says Gerlach. This is the third year Nashi Orchard has released a community-sourced cider called Issho Ni which means “join together” in Japanese.

Backyard Bounty

A similar ethos has sparked cidermakers across the Pacific Northwest to rally their community and add a rich layer to the craft—one that celebrates sustainability, sense of place, and giving back.

Sean Kelly of WildCraft Cider Works in Eugene launched his first community apple drive in 2015. “Eugene is a mecca for backyard fruit trees,” he says, and from August through November the cidery invited enthusiasts to bring by boxes of fruit—pears, plums and apples. Each box equaled a voucher for either a pint of finished cider or a quart of fresh juice.

“It was like bartering, but also encouraging people to use the fruit they have,” says Kelly. In February, the cidery hosted a citywide bash for the 28-varital cider made from community-sourced urban fruit. “We had 42 different locations pouring the cider, and 500 gallons to spread out amongst the town,” says Kelly. Bringing the community together, says Kelly, was a catalyst for this cider project.

Like Gerlach, who donates part of the proceeds of his community cider to a Vashon Island non-profit, Kelly gave ten percent of all community cider sales to the Long Tom Watershed Council, in addition to one dollar from each pint sold at participating businesses.

Since harvesting forgotten fruit is part of WildCraft’s mission, the community-sourced apple drive was a natural step. The majority of the apples Kelly uses are from wild-harvest efforts—this means gleaning from urban fruit trees, abandoned orchards, hiking trails and neighboring backyards.

Apple Collection

It’s a kindred passion for foraging that led David White of Whitewood Cider in Olympia to bottle his small-batch South Sounder Cider.

“Before receiving a fancy title and some prestige, foraging the community where I live was how I first started collecting apples and making cider,” says White. “It’s a shame how much fruit actually goes to waste each year,” he adds.

For his community cider, he calls on friends and local farms, and picks from abandoned trees or trees in nearby backyards where he finds owners who are happy to be relieved of the yearly chore of juggling fallen fruit.

In the past, White has harvested nearly 3,200 pounds of fruit, which equals about 250 gallons of cider. All of the varieties are either heirloom apples, or an enchanting mystery. “We did get some quince in the 2015 harvest and used it in the project, so I’m looking forward to the results of the additional flavor and tannins,” White says.

Crystie Kisler of Finnriver Farm and Cidery exemplifies the spirit of “community-sourced” cider in the tiny town of Chimacum, Washington. The idea for their Farmstead cider hails back to about five years ago, when tasting room visitors would frequently offer up their old, ugly backyard apples.

“We got very excited to learn about all of these old and often mysterious apple trees in backyards and homesteads all around us, and about the idea creating a community cider that represented the diversity of apples from across our region,” says Kisler. “For us, it’s a celebration of both the people and the trees in our place.”

After the first year of inviting the public to bring backyard apples to the farm, Kisler was struck by a sense of delight people shared when they came by to drop off their apples that were too bitter or bizarre.

Now tradition, the cidery launches a “Calling All Apples Campaign” each autumn—this overlaps with a World Apple Day Celebration at the farm with live music, country dancers, apple identification, orchard walks and more. To reciprocate the generosity of the community, Finnriver contributes ten cents on every bottle sold back to local food banks.

Urban Fruit

As community-sourced cider takes root, new partnerships with local non-profits and food banks emerge. “We were first approached by City Fruit, a Seattle non-profit that promotes the cultivation of urban fruit trees about working with them on a cider,” says Brent Miles of Seattle Cider Co.

Each year, City Fruit harvests from local tree owners and public orchards to secure and donate fresh fruit to local food banks. The nonprofit had a record-breaking year in 2014 with nearly 28,000 pounds of fruit harvested, including 5,892 pounds from public orchards. But bruised fruit—or excess fruit, when food banks reach capacity, is composted. Depending on the year, this could amount to thousands of pounds of fruit that could be used.

“They contacted us to see if we would be able to use the apples they couldn’t give to food banks and we jumped at the chance,” says Miles. “We’re excited about so many things,” he adds. “Being able to use 100% Seattle apples in the cider, working hand in hand with such a wonderful organization, and making something tasty out of apples that would have gone to waste,” he says.

One of the company values for Seattle Cider is collaboration, Miles adds, and the project with City Fruit is the essence of what they strive for.With the release of the City Fruit cider this spring, the cidery will donate a portion of the proceeds from each bottle to City Fruit to help them with next year’s harvest and their ongoing needs.

Helpful Harvests

Meanwhile, Kristen Needham of Sea Cider in Saanichton, British Columbia launched a community-sourced cider after she was approached by Life Cycles, a local non-profit that advocates for food security and education. Their programs range from managing community orchards, to creating school gardens and saving seeds.

“They also have something called the Fruit Tree Project, where volunteers go out and pick fruit throughout the season that would otherwise go to waste,” says Needham. Each year, the project harvests between 30,000 to 40,000 pounds of fruit from privately owned trees throughout the city of Victoria. The bounty is shared among the homeowners, volunteers, food banks, and community organizations, but even then, there can still be a surplus of apples.

More than a decade ago, the non-profit asked Needham if she would consider using some of the excess fruit in a cider, and in turn, gifting some of the proceeds to the organization. “The opportunity struck a chord with me personally,” she says. Before pursuing a career in cider, Needham worked as an international development consultant in Ethiopia focusing on food security.

“I feel strongly about food security in general,” she says. “Victoria is completely different than Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), but this partnership is a way for me to stay involved in that work and make a difference.”

The first year they made the cider, the mixed apples included King of Tonkins, Northern Spy, Spartans and a whole mystery batch—the result was titled Kings & Spies. Each year since, the make-up of the cider changes slightly depending on what the harvest brings. One constant, though, is that after pressing the apples, Needham ferments the juice with Champagne yeast to induce malolactic fermentation. She finds this yields an aromatic, Italian-style sparkling cider.

In addition to fruit from Life Cycles, the cider includes a smattering of heirloom apples from neighboring tree owners interested in contributing fruit. “Locally, people love it,” says Needham. “They come into the cider house excited because their apples are in our cider,” she adds. “There’s a feeling of community ownership.”

In the Pacific Northwest, the story of cider continues to flourish—its leading characters defined by quality, community, sustainability. Or as Gerlach from Nashi Orchards proclaims, “make cider and make a difference.”