Timberline Lodge stays close to home with a new rancher-direct beef program

Gate to Plate: Timberline Lodge stays close to home with a new rancher-direct beef program

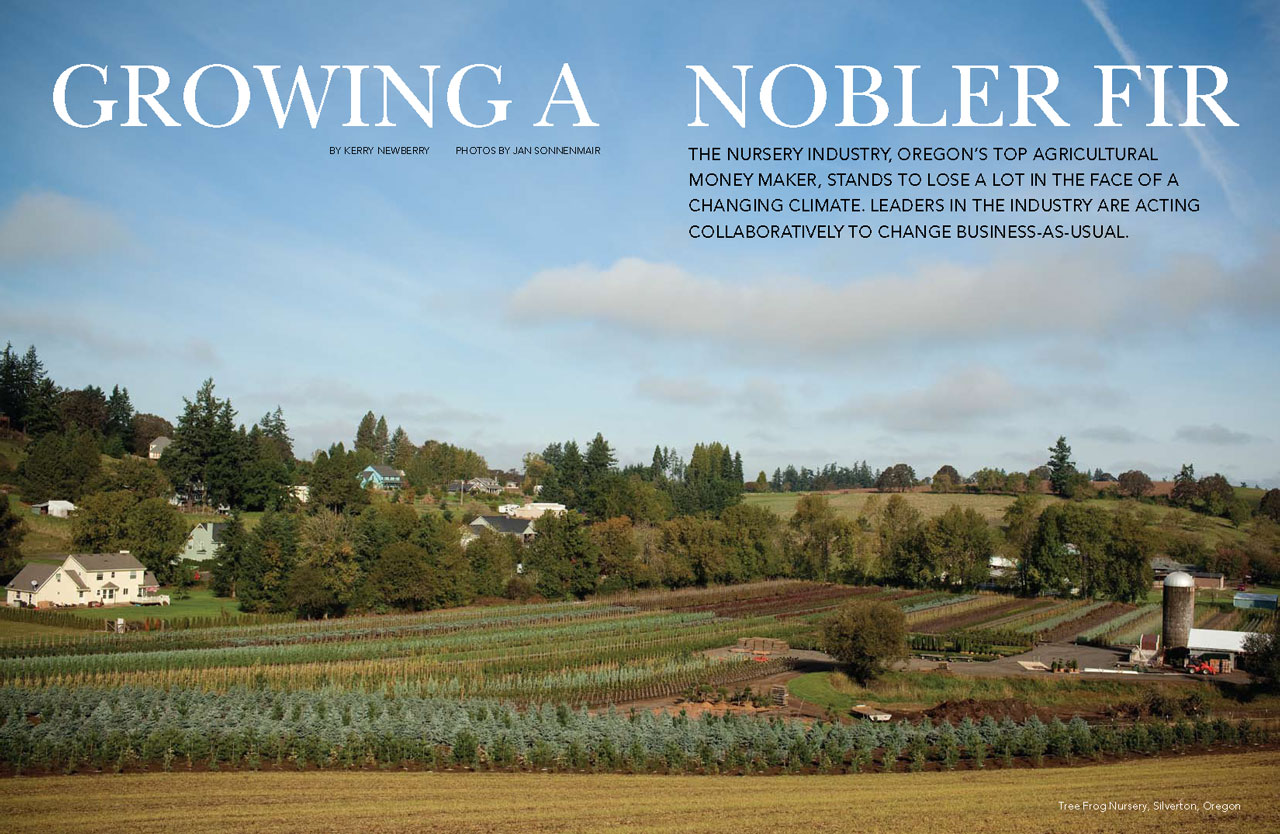

At first glance, the landscape evokes an Edward Hopper painting. A saturated sky so blue and bright, low mountains in the distance, a lonesome barn, and gently rolling grasses dotted with cows. But this is a modern-day snapshot from Grass Valley (population less than 200), a blink-of-an-eye ranching town that makes up part of Oregon’s heartland.

It’s mid-afternoon on a Saturday, and second-generation rancher and farmer Rory Wilson cruises by amber fields to check on his cows. He was up before sunrise and has already fed the family horses — his two daughters barrel-race in local competitions — and harvested more than 100 acres of safflower.

Farming has always required long days of hard work, but today, it also helps to have an entrepreneurial spirit. For Rory and his business partner, Keith Nantz, that led to forming Deschutes River Beef, a business enterprise that centers on their humanely raised cows. A few years ago, the two ranchers met through the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association and rallied around a shared passion for sustainable ranching and pasture-raised cattle.

Rory climbs out of his sliver pickup truck and eases over a low, woven-wire fence into a vast pasture, where mellow Aberdeen Angus cattle cluster in groups of two or three, like teens at a high school dance. Some slowly chew wheat stubble grass; others appear to be soaking up the view. A few stand side by side with newborn doe-eyed calves.

“Hey, Cutie, how are you,” he calls out in alto singsong. At first, it’s a somewhat surprising sound from a rancher the size of a linebacker. One of the onyx-black cows looks up. Rory walks over and scratches Cutie’s thick, hairy forehead. Cutie was named and bottle-fed by his daughters after the calf was abandoned by her mother. “We’ll keep her here for forever,” he says.

Rory and Keith raise their cattle on wide-open pastures, where they graze on a precise mixture of 14 different species of plants, including grasses and vegetables like collard greens and clover, radishes and turnips.. Keith calls it the “caviar of grasses.” Since 2008, he’s been exploring the relationship between soil vitality and rumen health in cows.

He’s observed that healthy soil makes for healthier cows. For one, it eliminates the need for fertilizers and pesticides. And two: it builds a habitat for microorganisms that are essential for breaking down the food into nutrients the cows can use. “Our cows have a symbiotic relationship with their pasture,” he says. “So what we try to do is put life back into the soil.”

In addition to rich crop diversity, and pasture rotation, the ranchers focus on raising the cows in a low stress environment. They wean their calves when they are about 8 or 9 months old, using a fence line method which creates minimal stress. And when handling the cattle, they follow the philosophy of animal behaviorist Temple Grandin and stockman Bud Williams.

“I firmly believe that with cattle the slower you go, the faster you can get it done,” says Keith.

Between the two ranchers, they raise cattle on 3,700 acres of pasture, with pockets of land near Grass Valley, Maupin, Condon, Dufur, and Scappoose.

In spring 2014, the two ranchers partnered with Timberline Lodge, a destination ski resort perched 6,000 feet atop the slope of Mt. Hood, for a gate-to-plate program. “How it began was happenchance,” says Executive Chef Jason Stoller Smith, who oversees the seven restaurants at the lodge.

Scott Skellenger, the assistant general manager at the lodge, has a small farm in Maupin. He was buying hay from Rory and Keith to feed his horses and small herd of goats. “I grew up on a farm and we never bought meat from stores,” he says, “we either raised it or traded with whoever had the best product in the area.” When he and Keith were unloading hay and talking about the cattle program, he saw a natural connection for the ranchers and the lodge.

Jason visited the pastures in Maupin, a scenic 45-minute drive from the lodge (without winter snow). Then he tasted some of the beef Rory and Keith produced.

“The flavor is amazing,” he says. “I like grass-fed beef; it’s a stronger beef, and the taste really sticks around, but I like the fact that they tone this down a bit by finishing the cattle on barley grains. I also believe in what they are doing on their farms. Sometimes you meet people who are passionate about what they do, and you don’t want to leave their side because you want to surround yourself with that.”

A few months later, Timberline Lodge purchased 52 head of cattle for their proprietary gate-to-plate beef program. “With our cooking, we are trying to communicate a sense of place,” says Jason. “It was a natural transition, since we already work with local and sustainably produced food — the fruits, vegetables, wine, and beer — and now one of the larger proteins with beef.”

One of the biggest challenges small cattle farmers face with direct sales is finding customers that can utilize a whole cow. “If we don’t have a customer for every piece, we get stuck with some of the lower end cuts that aren’t as familiar or easily used,” says Keith. ,”So we took that hurdle to Jason and asked how can we overcome this?”

Jason says it’s a challenge he’s always wanted to take on but was never able to tackle before because of the size constraints that come with most small restaurants. “I’ve butchered whole pigs, and that’s a lot of meat to work with, but there are avenues for it,” he says. “With a cow, it’s a different story because it’s so massive.”

What makes the program feasible for Timberline is that the lodge sees 2 million visitors a year and manages seven restaurants that include a formal dining room, casual pubs, cafes, and a brewery. “During the height of season, when all restaurants are open and full, we are feeding about 3,000 guests a day,” says Jason.

In July 2016, Jason brought in the first whole cow from the partnership and, since then, has received one cow every week. After dry-aging for 21 days, the 750-plus pounds of meat are broken down, a process that usually takes, at minimum, a full day. “We are able to utilize the whole animal, and we minimize waste as much as we can,” says Jason.

A variety of thick-cut steaks and slow-cooked roasts head to the Cascade Dining Room. Meanwhile, the Mt. Hood Brewing Company serves up beef burgers, and braised cuts are offered in various dishes in the Wy’East Café.

The bones, trim, off-cuts, and organ meats are used for stock, sausage, charcuterie, and stews. Even all of the fat is reduced down and used in baking desserts or for dipping bread. “I’ve been cooking in restaurants for 30 years,” says Jason. “What I’m excited about is that I never thought I could do something like this. It’s sustainable, economically smart, and is implementing social change on a deeper level.”

By partnering with Deschutes River Beef, Timberline eliminated several parts of the typical chain of production. “We cut the middleman out so we can focus on quality,” says Jason. “We can raise the quality of our beef without changing our prices.”

The same statement rings true on the ranching side. “We are with these cattle through their whole life cycle,” says Rory, meaning that Deschutes’ cows aren’t corralled to auction, sold to another farm to finish in a feed lot, moved again to a second acution, then sold to a final large processing plant. “We are doing everything here in our community.”

“Plus, people want local beef,” says Keith. “They want to know where it comes from and how it was raised, they want to know there’s good animal husbandry behind it.”

Carbonnade Flamande

By Jason Stoller Smith, Executive Chef, Timberline Lodge

Recipe

2 pounds boneless beef short ribs, cut into 2-inch chunks

1/4 cup seasoned flour

1/4 cup butter

1/4 cup applewood bacon, thinly sliced

4 cloves garlic, finely sliced

1 large onion, julienne

2 cups Mt. Hood Brewing Company’s “Voeden Glacier” barrel-aged beer or (if you must) any other Belgian-style ale

1 cup natural beef stock

2 tablespoons brown sugar

2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

1 tablespoon minced fresh thyme

1 tablespoon minced fresh parsley

1/2 tablespoon minced fresh tarragon

1 bay leaf

2 large Honeycrisp apples, peeled, cored, and cut into wedges

Pinch of kosher salt and some fresh ground pepper.

Steps

Preheat oven to 325°F. Heat a thick braising pan on the stovetop over high heat. Toss short ribs in seasoned flour. Add butter to braising pan and heat until browned and smoking hot. Add short ribs, in small batches, taking care not to crowd the pan and to maintain a hot temperature. Remove short ribs once browned.

Add bacon to pan and stir occasionally until cooked through but not browned. Add garlic to the bacon and cook briefly before adding the onions. Cook onions just until translucent and then return the browned short rib pieces to the pot. Add the beer and bring to a boil. Add remaining ingredients, except the apples, and raise temperature just to below boiling.

Cover braising pan and put in the oven for about an hour until short ribs are tender but not falling apart. Add apples and return to oven, cooking briefly just to cook the apples through. Correct seasoning and enjoy with more beer and crusty bread.

Edible Portland | January/February 2017

Click here to read on the Edible Portland website https://edibleportland.com/timberline-lodge-proprietary-beef-program/.